Casual Grains

My wife says I have an addictive personality, and she’s right. I am fully addicted to film photography, and have been for over three years. The specific split-second I got addicted to film photography was when I picked up my dad’s old Olympus OM-1, pressed the shutter, and the mirror slap gave a smooth springy recoil. That recoil was what did it for me.

For many years digital cameras had conditioned me to think cameras are machines that generate 0s and 1s, which then get translated into digital imagery by the magic of computing; but the moment I could feel the physical recoil of the shutter, it was no longer binary wizardry. I loved that the camera was fully mechanical, and not only was it theory, but I could feel the mechanisms in my hands. Taking a photograph was a tactile experience, from loading film to turning shutter speed dials and adjusting the aperture, I couldn’t rely on a machine to do the hard work; it was all down to me, but it made a successful image that much more rewarding. I was no longer a passenger in the image-making process, I was the driver.

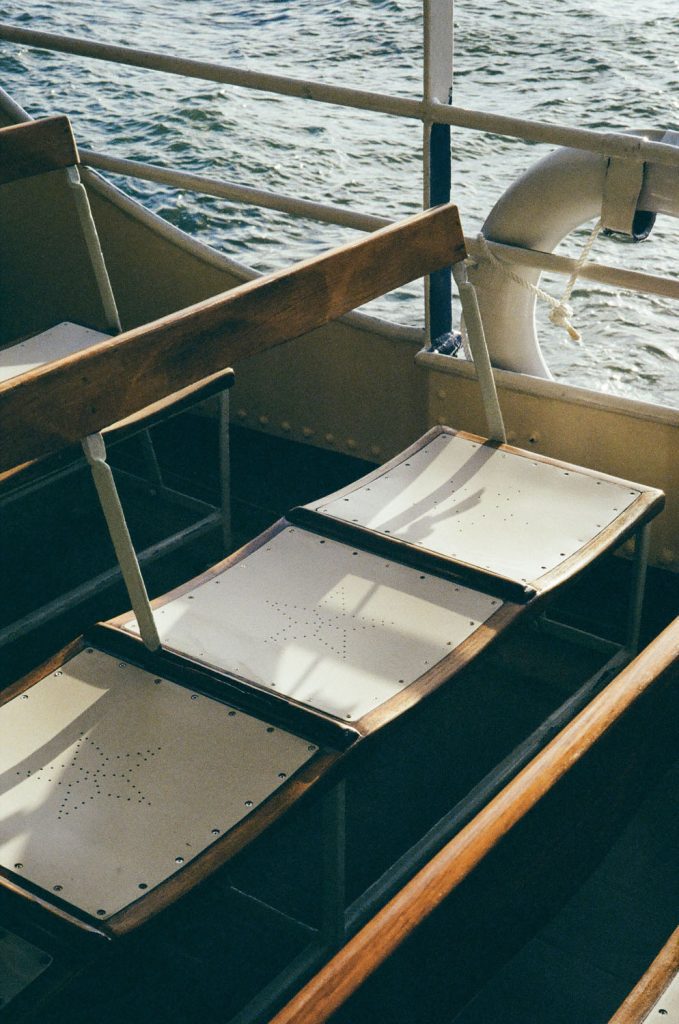

Olympus OM-1 F.Zuiko 50mm f1.8 Fujicolor Pro400H

Now, if the tactile experience of analog cameras didn’t have me hooked enough, the film grains certainly did. There’s something special about an image made up of grains instead of pixels. If an image is pixelated it seems low-quality and tacky, but when an image is grainy it just seems more authentic. The first time I zoomed into a film scan, I was mesmerised by the grains. I thought to myself: someone figured out the science behind putting silver halide crystals on top of a piece of plastic, and somehow through exposure to light and chemical reaction would lead to a physical image. How crazy is that? The grains represented physical imaging, not some binary wizardry, but the magic of actual science.

We live in a world where the images presented around us are overly perfected, selling us an unattainable version of ‘reality’. Film photography however represents the antithesis; it is authentic, imperfect and raw, and I was drawn to how faithfully it portrays reality with a touch of nostalgia. I also love the process of shooting film. I no longer live inside the screen of my camera, taking and retaking the same shot until I perfect a moment. Instead, I take one shot, move on, and continue to be immersed in the world. It is incredibly freeing when you cannot receive immediate feedback; it forces you to let go of the results, and you get to focus on the process instead.

Like many people getting into film photography, I quickly developed the famous GAS (Gear Acquisition Syndrome). I knew I would eventually work my way up to a couple of “final destination” cameras, but in my early exploration period, I truly enjoyed a few low-cost cameras, including the Yashica Electro 35 GT, Olympus 35UC and Nikon Zoom310 AF. However, I feel like I have now settled with the Contax 139Q as my go-to SLR and Leica M3 as my go-to rangefinder.

At the risk of making it a less under-the-radar series, I’m going to sing some praises to the Contax SLR line of cameras. The best part is definitely the full collection of Zeiss lenses, made to the highest quality and are superb value all around. The control of the camera is no-frills, intuitive, and it’s stylish as heck. They say the best camera is the one you have with you, and a stylish-looking camera is one you’ll always want to carry.

Compared with the more precise-framing of SLRs, rangefinders offer a much quicker and immersive street-photography experience, and ever since shooting with the M3, it has become more of a second nature. Once I got familiar with the patch-focus mechanism and using Sunny 16 as a basis for exposure, I found an effortless flow in the street. Shooting the M3 is a truly enjoyable experience, enhanced only by the buttery smooth operation, of a camera that is remarkably almost 70 years old, still operating on a top-of-the-class level.

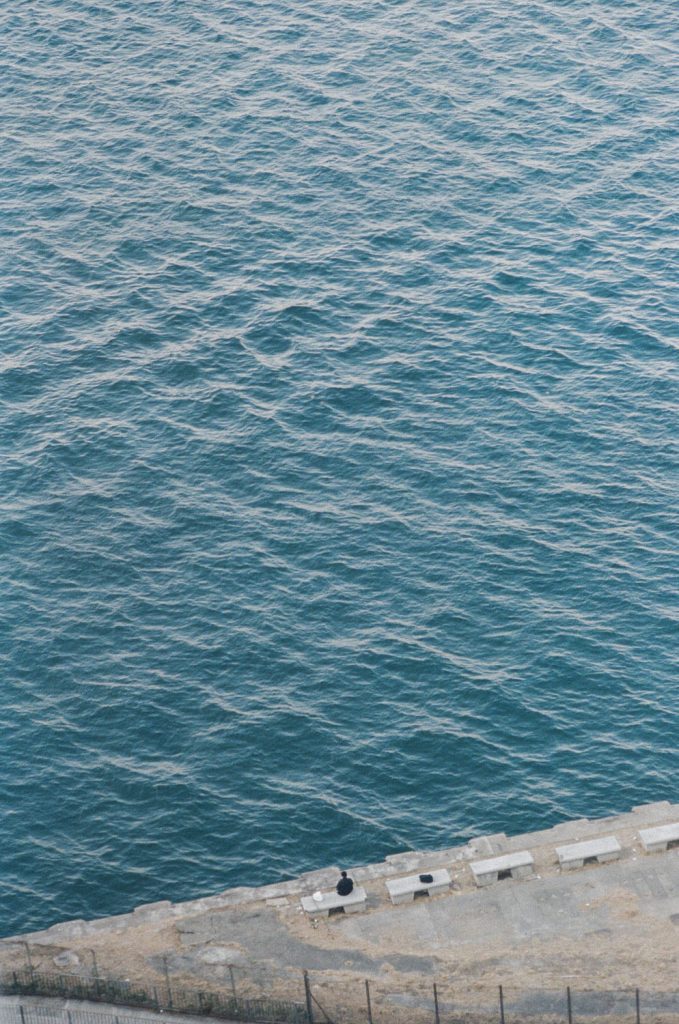

I have been shooting film since early 2020, which has coincided with a lot of turbulence and unfamiliarity in my beloved hometown of Hong Kong. Through COVID and all the changes we’re seeing, film photography has allowed me to capture sentiments of home that I often cannot express with words, to document the important things that make up our cultural identity, and allow me to process my complex feelings through wandering the streets of Hong Kong. Suffice it to say that film has become my therapy and has given me a lot of balance in life. I found minimalistic and quiet scenes calming, and instinctually I try to capture those moments. For an often-overwhelming place like Hong Kong, clean compositions don’t come by easily, but when they do it creates an interesting visual paradox.

About 18 months into shooting film, I decided to start a film photography account on Instagram. On one hand, I wanted to share my images, and like many wanted to have a separate account for that; on the other hand, I wanted to share about the various topics of film photography, and to some degree help demystify it for the growing demographic of film shooters. I had spent so much time learning about film stocks, vintage cameras and the process of shooting film, that I wanted to help those starting out, or those interested in improving their film photography to take the next step. I figured it was a casual hobby, so I decided to call it Casual Grains, because I believe film should be fun, and I didn’t want the pressure of running a serious film photography account. Funnily enough, I’m actually not casual about it at all.

Nowadays, I never leave home without a camera and multiple rolls of film on hand. I almost feel insecure if I’m unable to capture the things and scenes I encounter. Street photography is often reactive, I react to what the world presents, and I curate accordingly, but I’m also learning to be more proactive in finding a narrative. Lately, I’ve been interested in the smaller things and scenes that make up the cultural identity of a people, more specifically that of my city of Hong Kong. I wanted those who are unfamiliar with us to know we’re more than skylines and neon signs, and I want those who have an attachment to this city to be reminded of what are the things that make us us.

Moving forward, I hope to be able to work on a new exhibition, as well as apply film photography in more commercial projects. I also want to continue to play a role in enriching the film photography community; whether it is through content, projects or even products, I see a wonderfully diverse demographic that will continue to grow and blossom. Yeah, these film grains are not so casual after all.

Mamiya 645 Sekor-C 80mm f1.9 Kodak Gold 200

Text and Photos by Enoch Ho